Maria Zambrano – The discovery that philosophy steps out of life

Maria Zambrano (1904-1991) was a Spanish philosopher who wrote in a unique poetic style. Her father was an intellectual, and she was interested in philosophy from an early age. She studied in Madrid philosophy with Ortega and others, and was active against the dictatorship of that time. She then left for Latin America, and returned to Spain only many years later.

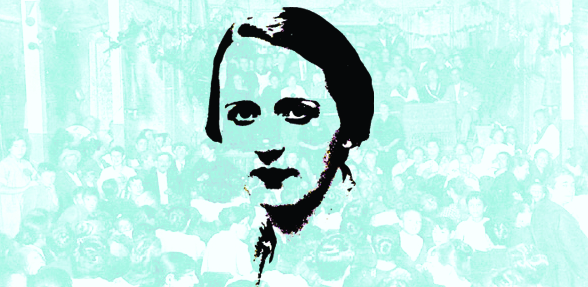

The following passage is from Zambrano’s book Delirium and Destiny: A Spaniard in her twenties (1953), from the chapter “Remembering the future.” This book is a poetic autobiography of her early years. Although she uses the third-person (“she”), she is talking about herself. Here Zambrano describes a public meeting against the Spanish dictator Primo de Rivera. In this meeting she experienced harmony and togetherness among everybody in the room – the simple workers, the respectable professors, and the young activists – an experience that was very different from doing philosophy. This was a powerful experience of being in life and with life, of harmony and togetherness with others. This realization, that philosophy steps outside life, away from “here,” and looks at life from a distance, can be found throughout Zambrano’s writings. See, for example, her text on Agora’s “Philosophizing” page (December 2015):

https://www.philopractice.org/web/topics-2015/philosophizing#Zambrano

«The hall where they talked to the cigar workers was full. She was the last on the program; two male colleagues had spoken before her. Almost all the leaders from the earlier meeting were there. This was not really a political “meeting.” But what was it? There may never be another event precisely like it. They spoke almost without a topic, as they spoke among themselves, in their own way. And the women – all of the cigar workers were women – understood perfectly. […] There was perfect harmony between the respectable men – the famous men of the sciences, the Spanish university, Spanish letters – and the cigar workers, and the young people of her group. The words only provided the tempo in a concert improvised by a Mozart-like musician.

They felt happy when they left the headquarters of the cigar workers’ union. Her own happiness was similar to the feeling that had filled her soul a few times when she had understood something in philosophy. But in the case of philosophical understanding, her happiness was like a beam of light flooding her mind, and her entire soul would be stimulated, although this could not last for a long time. Afterwards, what she understood would slowly become diffused, even become apparent, because she needed a long time to see its implications and consequences, to see the “order and connections” established by thought […] In contrast, this happiness about the “concert” with the cigar workers, about the unplanned harmony, came from her heart, from the darkest depth of her life. The important thing was not that she had spoken to these women but that she had spoken WITH them, with the heart of Madrid, as if there were no social classes. The pulse of Spain, its throbbing, created that harmony, that living silence where words felt like music. […]

This pulse, the peaceful and passionate vibration of a life that transcended her own life, took her, seized her, and led her toward the threshold of her own life. Because she had never even dreamed of abandoning philosophy, or the philosophy courses which she had recently started giving at Instituto Escuela […]

Now, suddenly she found herself “here,” without disciples or teachers, without a group of colleagues, without anything, aware of her pulse, only her own pulse, like a bird that wants to pull out the heavy bars of its cage. She was at a point of suffocation after breathing so widely and deeply, in the pure oxygen of her new life, as she rushed to get those ideas into her blood immediately, into everyone’s blood. She was falling, although from trying to look at something new.

[…]

Why had she studied philosophy, which she did not love? Perhaps to fill an initial void, or an early void which she experienced as a very young woman? Hadn’t philosophy been born, not only in her emotions, but also in the world, “because of the lack of something else”? What have you lost when you keep searching for [philosophical] knowledge, a knowledge without consolation, which accepts the object’s refusal to give itself but at the same time discovers that the object is necessary, and so discovers an “aporia” (confusion, puzzle)?»

Posted in November 2017