It is not hard to imagine what we expect to find in a philosophical practitioner’s library: Hardcover classics like Aristotle’s Nichomahean Ethics, less known writings, and, of course, the works of one’s beloved philosophers. Probably, we would also find works of literature. Some of them, I guess, could claim for themselves the status of a philosophical work.

Consider, for example, The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, a major novel of modern literature. Hans Castorp, its young protagonist, as Alexander Nehamas has pointed out, provides an image of Nietzsche’s ‘philosophers of the future’ or ‘experimental philosophers’.

Literary prose, poetry and drama can express universal issues by means of particularity. Sometimes they convincingly concretize what might seem often highly abstract in theory. All this qualifies literature as a great source of inspiration. What’s more, for some philosophical practitioners literature becomes what Petra von Morstein calls «Lehrmeisterin philosophischer Praxis» [a teacher of philosophical practice].

From the very beginning, there has been such a strong bond between literature and philosophy that Plato felt the urge to denounce it, allegedly, for the sake of philosophy. One of the recurrent questions of modern aesthetics, whether literature is a better philosophy, proves nothing but a most intimate relationship or, at least, for the skeptic ones, some elective affinity.

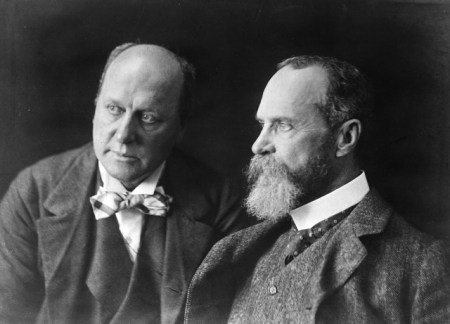

One of Ran Lahav’s reflections is dedicated to William James. We could remember as well his brother Henry, as Robert Pippin does in his Henry James and Modern Moral Life. A famous photograph shows William and Henry at a mature age, sitting next to each other, looking both at the same direction. One could hardly find a better image for the family bond between philosophy and literature.